Who Is an Artist Who Used a Dog Head Stamp in His Art

| Eric Gill ARA RDI | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait | |

| Born | Arthur Eric Rowton Gill (1882-02-22)22 Feb 1882 Brighton, Sussex, England |

| Died | 17 November 1940(1940-eleven-17) (aged 58) Middlesex, England |

| Instruction |

|

| Known for | Sculpture, typography |

| Move | Arts and Crafts motility |

Arthur Eric Rowton Gill ARA RDI (22 Feb 1882 – 17 November 1940) was an English sculptor, letter cutter, typeface designer, and printmaker. Although the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography describes Gill equally ″the greatest artist-craftsman of the twentieth century: a letter-cutter and type designer of genius″, following revelations of his sexual abuse of two of his daughters, he remains a figure of considerable controversy.

Gill was born in Brighton and grew up in Chichester, where he attended the local college before moving to London. There he became an amateur with a business firm of ecclesiastical architects and took evening classes in stone masonry and calligraphy. Gill abandoned his architectural preparation and set a business cut memorial inscriptions for buildings and headstones. He also began designing chapter headings and title pages for books.

As a young man, Gill was a member of the Fabian Club, but afterward resigned. Initially identifying with the Craft Movement by 1907 he was lecturing and campaigning against the movements perceived failings. He became a Roman Catholic in 1913 and remained so for the rest of his life. Gill established a succession of arts and crafts communities, each with a chapel at its heart and with an accent on transmission labour as opposed to more modern industrial methods. The first of these communities was at Ditchling in Sussex where Gill established the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic for Cosmic craftsmen. Many members of the Guild, including Gill, were as well members of the Third Society of St. Dominic, a lay sectionalisation of the Dominican Order. At Ditchling Gill, and his assistants, created several notable war memorials including those at Chirk in north Wales and at Trumpington near Cambridge forth with numerous works on religious subjects.

In 1924, the Gill family left Ditchling and moved to an isolated, disused monastery at Capel-y-ffin in the Black Mountains of Wales. The isolation of Capel-y-ffin suited Gill's wish to distance himself from what he regarded every bit an increasingly secular and industrialised guild and his time in that location proved to be among the virtually productive of his creative career. At Capel, Gill made the sculptures The Sleeping Christ (1925), Deposition (1925) and Mankind (1927). He created engravings for a series of books published by the Golden Cockerel Press, considered among the finest of their kind, and information technology was at Capel that he designed the typefaces Perpetua, Gill Sans and Solus. After four years at Capel, Gill and his family moved into a quadrangle of backdrop at Speen in Buckinghamshire. From there, in the terminal decade of his life Gill became an architectural sculptor of some fame, creating large, high profile, works for primal London buildings including both the headquarters of the BBC and the forerunner of London Underground. His mammoth frieze, The Creation of Human, was the British Governments' gift to new League of Nations edifice in Geneva. Despite failing health Gill was active as a sculptor until the last weeks of his life, leaving several works to be completed by his assistants subsequently his death.

Gill was a prolific author on religious and social matters, with some 300 printed works including books and pamphlets to his name. He frequently courted controversy with his opposition to industrialisation, mod commerce and the use of machinery in both the home and workplace. In the years preceding World War Ii, he embraced pacifism and left-wing causes.

Gill's religious beliefs did not limit his sexual activeness, which included several extramarital affairs. His religious views and subject area matter contrast with his deviant sexual behaviour, including, every bit described in his personal diaries, his sexual abuse of his daughters, an incestuous human relationship with at least one of his sisters and sexual experiments with his canis familiaris. Since these revelations became public in 1989, in that location have been a number of calls for works past Gill to be removed from public buildings and fine art collections.

Biography [edit]

Early life [edit]

Eric Gill was born in 1882 in Hamilton Road, Brighton, the 2nd of the thirteen children of the Reverend Arthur Tidman Gill and (Cicely) Rose King (d. 1929), formerly a professional singer of light opera nether the name Rose le Roi.[i] Arthur Tidman Gill had left the Congregational church in 1878 over doctrinal disagreements and became a minister of a sect of Calvinist Methodists known as the Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion.[2] : vii Arthur was born in the South Seas, where his father, George Gill, was a Congregational minister and missionary.[2] : 5 Eric Gill was the elder brother of the graphic artist MacDonald "Max" Gill (1884–1947).[1] Two of his other brothers, Romney and Cecil, became Anglican missionaries while their sis, Madeline, became a nun and too undertook missionary work.[two] : five

In 1897, the family moved to Chichester, when Arthur Tidman Gill left the Countess of Huntingdon'south Connexion, became a mature student at Chichester Theological College and joined the Church of England.[one] [two] : 19 Eric Gill studied at Chichester Technical and Fine art School, where he won a Queen's Prize for perspective drawing and developed a passion for lettering.[2] : 26 Later in his life, Gill cited the Norman and medieval carved stone panels in Chichester Cathedral as a major influence on his sculpture.[three] [4] In 1900 Gill became disillusioned with Chichester and moved to London to railroad train as an architect with the do of W. D. Caröe, specialists in ecclesiastical compages with a large office close to Westminster Abbey.[1]

London 1900–1907 [edit]

Frustrated with his architectural grooming, Gill took evening classes in stonemasonry at the Westminster Technical Institute and, from 1901, in calligraphy at the Central School of Arts and Crafts while standing to piece of work at Caröe's.[v] The calligraphy course was run past Edward Johnston, creator of the London Cloak-and-dagger typeface, who became a stiff and lasting influence on Gill.[2] : 42 For a year, until 1903, Gill and Johnston shared lodgings at Lincoln'south Inn in central London.[ii] : 49

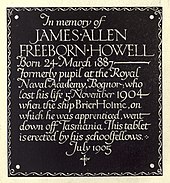

Rubbing of a memorial bronze created past Eric and Max Gill in 1905

During 1903, Gill gave up grooming in architecture to go a calligrapher, letter-cutter and awe-inspiring mason.[vi] Afterwards making a copy of a small stone tablet from Westminster Abbey, Gill's first public inscription was for a stone memorial tablet, to a Percy Joseph Hiscock, in Chichester Cathedral.[2] : 45 Through a contact at the Central Schoolhouse, Gill was employed to cut the inscription for a tombstone at Brookwood Cemetery in Surrey.[2] : 45 Other work quickly followed, including an inscription for Holy Trinity, Sloane Street, plus commissions from architects and private individuals, including Count Kessler.[two] : 93 Kessler, on Johnston's recommendation, employed Gill to pattern affiliate headings and title pages for the Insel Verlag publishling house.[5] W.H. Smith & Son employed Gill to pigment the lettering on the fascias of several of their bookshops including, in 1903, their Paris shop.[2] : 55 For a fourth dimension, Gill combined this piece of work with his job at Caröe's but eventually the calibration and frequency of these commissions required him to leave the company.[2] : 88 Later on Gill died, his brother, Evan, compiled an inventory of 762 inscriptions known to take been carved by him.[two] : 45

In 1904 Gill married Ethel Hester Moore (1878–1961), a old fine art student, later known as Mary, the daughter of a businessman who was likewise the caput verger at Chichester Cathedral.[2] : 31 Gill and Moore would eventually have three daughters and foster a son.[one] After a short period in Battersea, the couple moved into 20 Black King of beasts Lane, Hammersmith in due west London, near the, recently married, Johnstons' home on Hammersmith Terrace.[7] A number of artists associated with the Arts and Crafts move, including Emery Walker, T. J. Cobden-Sanderson and May Morris were already based in the area, as were a number of printing presses, notably the Doves Printing.[2] : 64 Gill formed a business partnership with Lawrence Christie and recruited a number of staff, including the xiv-year onetime Joseph Cribb, to work in his studio.[2] : 66 Gill began giving lectures at the Central School and taught courses in monumental masonary and lettering for stonemasons at the Paddington Establish.[2] : 102 In 1905 he was elected to the Arts and crafts Exhibition Society and joined the Fabian Society the following twelvemonth.[ii] : 101 Later a period of intense involvement with the Fabians, Gill became disillusioned with both them and the Arts and Craft movement. By 1907 he was writing and making speeches about the failures, both theoretical and practical, of the craft motility to resist the advance of mass-product.[ii] : 93

In his diaries, Gill records 2 affairs while living at Hammersmith. He had a brief affair with the family maid while his wife was pregnant and then a relationship with Lillian Meacham, who he met through the Fabian Society.[2] : 95 Gill and Meacham visited the Paris Opera and Chartres Cathedral together and when their matter concluded, she became an apprentice in Gill's workshop and remained a family friend throughout her life.[2] : 95

Ditchling Village 1907–1913 [edit]

In 1907, Gill moved with his family to Sopers, a house in the village of Ditchling in Sussex, which would later go the eye of an artists' community inspired by Gill. Although by April 1908 Gill had established a workshop in Ditchling and dissolved his business organization partnership with Lawrence Christie, he continued to spend considerable amounts of time in London visiting clients and delivering lectures, while his wife Ethel organised their household and smallholding in Sussex.[ii] : 120 In London, Gill would stay at his onetime lodgings in Lincoln's Inn with his brother Max or with his sis Gladys and Ernest Laughton, her future husband.[2] : 122 Gill continued to concentrate on lettering and inscriptions for stonework and employed a pupil for his signwriting business concern.[two] : 126 He also began to use wood engraving techniques for his book analogy work, notably for an 1907 edition of Homer for Count Kessler.[2] : 126

Late in 1909 Gill decided to become a sculptor.[2] : 126 Gill had always considered himself an artisan craftsman rather than an creative person. He rejected the usual sculpture technique of first making a model and so scaling up using a pointing machine, in favour of directly carving the last figure.[4] [8] His first sculptures included Madonna and Kid (1910), which the art critic Roger Fry described every bit a delineation of "pathetic lust",[9] and the well-nigh life-size work now known every bit Ecstasy (1911).[4] The models for Ecstasy were his sister Gladys Gill and her married man Ernest Laughton.[2] : 104 [ten] The incestuous relationships between Gill and Gladys that connected during their lives and had already began at this bespeak.[2] : 104 [4] At that place is also some bear witness, from Gill's ain writings, of an incestuous relationship with Angela, another of his sisters.[two] : 105 [10]

An early on admirer of Gill'south sculptures was William Rothenstein and he introduced Gill, who was fascinated past Indian temple sculptures, to the Ceylonese philosopher and art historian Ananda Coomaraswamy.[11] Along with his friend and collaborator Jacob Epstein, Gill planned the construction in the Sussex countryside of a colossal, mitt-carved monument in imitation of the big-scale structures at Gwalior Fort in Madhya Pradesh.[12] Throughout the 2d half of 1910, Epstein and Gill would met on an well-nigh daily basis, but eventually their friendship soured very desperately. Earlier in the year they had held long discussions with Rothenstein and other artists, including Augustus John and Ambrose McEvoy, about the formation of a religious brotherhood.[2] : 102 At Ditchling, Epstein worked on elements of Oscar Wilde's tomb in Pere Lachaise cemetery for which Gill designed the inscription before sending Joseph Cribb, who had moved to Ditchling in 1907, to Paris to cleave the lettering.[two] : 135 [13]

Gill had his kickoff sculpture exhibition in 1911 at the Chenil Gallery in London.[ix] Eight works by Gill were included in the Second Post-Impressionism Exhibition organised by Roger Fry at the Grafton Galleries in London during 1912 and 1913.[13]

By 1912, while Gill'south master source of income was from gravestone inscriptions, he had also carved a number of Madonna figures and was widely assumed, wrongly at that time, to be a Catholic artist. As such he was invited to an exhibition of Catholic art in Brussels and, on road, stayed for some days at the Benedictine monastery at Mont-César Abbey about Louvain.[2] : 94 Gill's experiences at Louvain, seeing the monks at prayer and hearing plainsong for the first time convinced him to go a Roman Catholic.[14] In February 1913, after religious instructions from English Benedictines, Gill and Ethel were received into the Catholic Church and Ethel changed her proper name to Mary.[2] : 147

Westminster Cathedral 1914-1918 [edit]

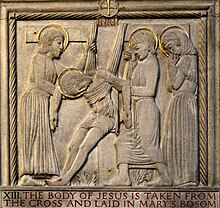

Westminster Cathedral, Stations of the Cross Thirteen

In 1913, after Gill and his wife became Roman Catholics they moved to Hopkin's Crank at Ditchling Mutual, 2 miles north of Ditchling hamlet.[1] There, Gill worked primarily for Cosmic clients, notably his 1914 commission for the 14 stations of the cross in Westminster Cathedral.[i] [15] Gill was an surprising option for the commission as he had only recently become a Catholic and had only been a sculptor for three years.[16] However he was prepared to do the piece of work quicker and for a lower fee than more established sculptors would.[xvi] Gill modelled both the Christ effigy in panel ten and a soldier in the second panel on himself.[xv] The Stations were not universally well received when they were erected with criticism of their simple appearance and how starkly they contrasted with the rest of the cathedral interior.[16] A minority, that eventually included Nikolaus Pevsner, praised their uncluttered blueprint and unsentimental treatment of the subject area.[sixteen] They are now considered among Gill's most achieved large calibration works.[ii] : 125 Afterwards, Gill submitted proposals for decorations and works in other parts of the Cathedral building and, eventually, his design for the Chapel of Saint George and the English Martyrs was commissioned.[sixteen]

Gill had been granted exemption from military machine service while working on the Stations of the Cross and when they were finished spent three months, from September 1918, as a driver at an RAF military camp in Dorset, before returning to Ditchling.[2] : 138

Ditchling Common 1918–1924 [edit]

Later Globe State of war I, together with Hilary Pepler and Desmond Chute, Gill founded a society association to promote the ethics of medieval, or pre-industrial, craft product, The Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic at Ditchling.[eight] [fourteen] The Order'due south accent was on transmission labour as opposed to more modern industrial methods, such that they did not use mechanised tools and considered craft working a form of holy worship.[14] All members of the Guild were Catholics and most, including Gill, were also members of the Third Order of St. Dominic, a lay division of the Dominican Society.[14] Lay members were non expected to follow the Dominicans daily Liturgy of the Hours, a schedule of prayers from the Angelus at 6am to Compline at 9pm, only the group at Ditchlıng, unusually, did so.[2] : 146 A chapel, designed by Gill, was built in the centre of the Order's workshops and a wooden cross, wıth a Christ figure carved by Gill, was erected on a nearby hill.[ii] : 147 Gill had also taken to wearing a habıt, often with a symbolic cord of chastity added.[2] : 143 In his family home, Gill determined that the household was to be gratis of modern appliances, with no bathroom, water drawn past a pump and cooking washed on a log burn. One invitee who brought a typewriter into the house was scolded for doing so.[two] : 127 The children did not attend school.[17]

Alongside the Social club, Pepler prepare up the St Dominic's Press with a 100-year old Stanhope printing that he bought.[5] The Press printed books and pamphlets promoting the ideals of the Guilds' traditional craft techniques and also provided an outlet for Gill's engravings and woodcut illustrations.[fourteen] Gill and Pepler together produced issues of The Game, a small journal, generally illustrated past Gill and containing manufactures on craft and social matters.[2] : 122 The views promoted by Gill and Pepler in The Game and their other publications were often deliberately provocative, anti-capitalist and opposed to industrialisation.[5]

Along with his Guild work and illustrations, Gill designed several war memorials in this period. These included the memorials at Trumpington in Cambridgeshire, at Chirk in north Wales, at Ditchling and the wall panel recording 228 names of the fallen in the ante-chapel at New College, Oxford.[ane] [18] [19] [20] Gill also created the memorial at Briantspuddle in Dorset and, with Chute and Hilary Stratton, the monument at S Harting.[21] [22] Beside the main entrance to the British Museum, Gill designed and carved, with Joseph Cribb, the memorial inscription to the museum staff killed in the conflict and for the Victoria and Albert Museum, again with Cribb, he created the state of war memorial in that museum'southward anteroom.[23] [24] Previously, in 1911, Gill had cut the inscription for the foundation stone of the British Museum'south new King Edward Vii edifice.[v] Gill's other significant work from this period was the Stations of the Cross that he carved, with Chute, for the Church of St Cuthbert in the Manningham area of Bradford.[25]

-

St. George, item of South Harting war memorial, West Sussex

-

Ditchling war memorial, Sussex

-

Chirk war memorial, Wrexham

-

Victoria & Albert Museum staff war memorial

-

Detail of Briantspuddle war memorial, Dorset

Commissioned to produce a state of war memorial for the Academy of Leeds, Gill produced a frieze depicting the Cleansing of the Temple but showing gimmicky merchants as the money-changers Jesus was driving from the Temple.[26] [27] While fully aware that this was an inappropriate subject for a war memorial and i likely to cause peachy offence in a commercial center such every bit Leeds, Gill persisted with the pattern regardless. The cartoon-like nature of the finished frieze, which included the Hound of St Dominic knocking over a cash till, merely added to the ferocity of the resulting uproar.[2] : 166

Even earlier the Leeds memorial controversy, Gill's series of illustrations that included the Nuptials of God, The Convert and Divine Lovers and his views on the sexual nature of Christianity were causing alarm inside the Roman Catholic hierarchy and distancing Gill from other members of the Ditchling community.[2] : 164 The series of life-drawings and prints of his daughters, including Daughter in Bath and Hair Combing done at Ditchling, were considered among Gill's finest works. The sexual abuse Gill was perpetrating on his 2 eldest daughters during the same period just became known after his expiry.[4]

A number of professional craft workers joined the community, such that by the early 1920s the customs had grown to 41 people, occupying several houses in the 20 acres surrounding the Club'south chapel and workshops.[2] : 148 Notable visitors to the Common included G. Thou. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc, whose Distributist ideas the Guild followed.[14] Some immature men who had been in gainsay in Globe War I came to stay for longer periods. These included Denis Tegetmeier, Reginald Lawson and the artist and poet David Jones, who was to become engaged for a time to Gill's second girl, Petra.[2] : 151

However, Gill became disillusioned with the direction of the Guild and roughshod out desperately with his close friend Pepler, partly over the latter'due south wish to aggrandize the community and form closer ties with Ditchling village and also because Gill's daughter, Betty, wanted to marry Pepler's son, David.[14] Gill resigned from the Social club in July 1924 and, after because a number of other locations in Britain and Ireland, moved his family to a deserted monastery in the Blackness Mountains of Wales.[2] : 170

Capel-y-ffin 1924–1928 [edit]

In Baronial 1924, the Gills left Ditchling and, with two other families, moved to a disused monastery, Llanthony Abbey, at Capel-y-ffin in the Black Mountains of Wales.[ii] : 179 The dilapidated building was loftier in an isolated valley about fourteen miles from Abergavenny. Finding the monastery chapel across repair, a new one was quickly built and a Benedictine monk from Caldey Abbey was assigned to the group to concord a daily Mass.[2] : 182 Donald Attwater arrived at Capel-y-ffin soon earlier the Gills, David Jones and René Hague, Joan Gill's futurity husband, all joined shortly later on.[2] : 182 Joseph Cribb did not make the movement to Wales but his younger brother, Lawrence Cribb (1898-1979), did and eventually became Gill's main assistant.[5]

Within a few weeks of arriving at Capel-y-ffin, Gill completed Degradation, a black marble torso of Christ, and made The Sleeping Christ, a stone head now in Manchester City Art Gallery.[2] : 185 In 1926 he completed a sculpture of Tobias and Sara for the library of St John's College, Oxford.[28] A state of war memorial altarpiece in oak relief for Rossall Schoolhouse was completed in 1927.[1]

When approached, in 1924, by Robert Gibbings to produce designs for the Golden Cockerel Printing which he and his wife, Moira, had recently acquired, Gill initially refused to work with the couple as they were not Catholics. Gill changed his heed when they sought to publish a book of poems by his sister Enid. The human relationship between Gill and the Gibbingses grew such that throughout the post-obit ten years Gill became the chief engraver and illustrator for the Gold Cockerel Press. Several of the resulting books, including The Song of Songs (1925), Troilus and Criseyde (1927), The Canterbury Tales (1928), and The Four Gospels (1931) are considered classics of specialist volume production.[2] : 187 Gill created striking designs that unified and integrated illustrations into the text and as well created a new typeface for the Press.[5] The erotic nature of The Song of Songs and of the illustrations for Edward Powys Mathers'due south Procreant Hymn caused considerable controversy in Roman Catholic circles and led to protracted arguments between Gill and members of the clergy.[two] : 211 [29] The Golden Cockerel printed four of Gill'south own books and he illustrated a further thirteen works for the press.[5] In add-on, between 1924 and his decease, Gill wrote 38 books and illustrated a further 28.[5]

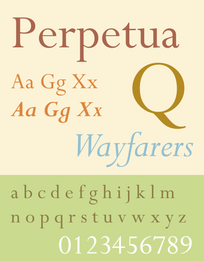

The other key working relationship Gill established while at Capel-y-ffin was with Stanley Morison, the Typographic Advisor to the Monotype Corporation. Morison persuaded Gill to utilize the skills and knowledge he had gained in alphabetic character cutting to fonts suitable for mechanical reproduction.[ii] : 187 It was at Capel that Gill designed the typefaces Perpetua (1925), Gill Sans (1927 onwards) and began work on Solus (1929).[1] Gill Sans is considered one of the well-nigh successful blazon-faces e'er designed and remains in wide spread use.[29]

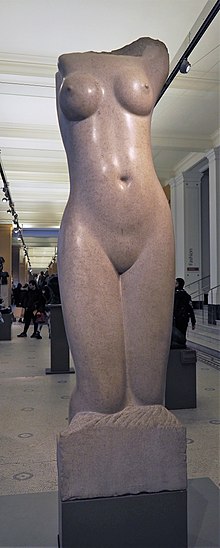

While living at Capel-y-ffin, Gill spent many weekends at Robert and Moira Gibbings habitation ın Waltham St Lawrence, enjoying the couple's anarchistic and hedonistic lifestyle.[two] : 191 He was also spending sizable amounts of time in Bristol with a group of immature intellectuals centred around Douglas Cleverdon, a bookseller who published and distributed some of Gill'due south writings.[two] : 192 From 1925 onwards, Gills' secretary, and mistress, was Elizabeth Nib. Pecker owned a villa set in several acres in the French Pyrenees at Salies-de-Béarn and which the Gills ofttimes visited.[two] : 205 The Gill family unit spent the winter of 1926-27 there, and which was where Gill did many of the engravings for Troilus and Criseyde.[2] : 215 For the last months of 1927 he worked in a studio in London at Glebe Place in Chelsea creating the sculpture originally known as Humanity and now chosen Mankind. The piece of work, a giant torso, was modelled by Angela Gill and shown at the Goupil Gallery in London, to considerable acclamation, earlier being purchased by the creative person Eric Kennington.[2] : 220 [30] Some years subsequently, Kennington offered the piece of work to Whipsnade Zoo. The zoo refused the offering and the work is now in the Tate drove but displayed at the Victoria and Albert Museum.[2] : 220 [viii]

It had been too impractical to transport the stone for Mankind to Capel-y-ffin and it was clear that the site had become too remote and isolated for Gill's increasing commercial workload and by May 1928 he was seeking a new home for his family and workshops.[2] : 221 [29]

-

Gill Sans

-

Joanna Nova

-

Perpetua

-

Golden Cockerel type

-

Iii typefaces by Gill

Pigotts, Buckinghamshire 1928-1934 [edit]

In October 1928, the Gill family moved to Pigotts at Speen, 5 miles from High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire. Effectually a quadrangle with a central hole were a large farmhouse housing Eric and Mary Gill, a cottage for Petra and her husband Denis Tegetmeier and some other for Joanna and René Hague. Stables and barns were converted to studios and workshops and to business firm press presses.[2] : 225 A chapel was fitted into one corner and licensed within six months for the saying of Mass.[ii] : 226

N Wind, St James'south Park Station, London

The success of his 1928 exhibition at the Goupil Gallery had raised Gill's profile considerably and led to Charles Holden commissioning him to lead a squad of five sculptors, including Henry Moore, in creating some of the external sculptures for the new headquarters building of the London Electrical Railway, the forerunner of London Hole-and-corner.[two] : 228 Gill started on the project within days of arriving at Pigotts and worked on site in London from November 1928 to cleave three of eight relief sculptures on the theme of The 4 Winds for the building.[ii] : 229

Art-Nonsense And Other Essays by Eric Gill was published in 1929 and marked the first commercial use of the Perpetua typeface. The frontispiece of the book had an engraving of Belle Sauvage, an paradigm of a naked women stepping out of some woods. The various versions of Belle Sauvage became among the most popular of Gill'due south illustrations and were modelled by Beatrice Warde, a historian of typography, an executive of the Monotype Corporation and sometimes Gill's lover.[2] : 232 By 1930 Gladys Gill had divorced her second married man after her get-go, Ernest Laughton, had existence killed in the Battle of the Somme, and she and Eric appear, from his diary entries, to accept resumed their incestuous relationship.[ii] : 239 Later that same twelvemonth the diaries tape what Gill chosen his 'experiments' with a domestic dog.[2] : 239 In September 1930 he was taken seriously sick with a diverseness of symptoms, including amnesia, and spent several weeks in hospital.[2] : 237

The following 2 years were among the nearly creatively accomplished of Gill's career, with several notable achievements. The Hague and Gill press was established at Pigotts in 1931 and eventually printed sixteen of Gill's own books and booklets while he also illustrated six other books for the company.[5] For the Hague and Gill press he created the Joanna typeface, which was eventually adapted for commercial employ past Monotype. He completed The Four Gospels, widely considered to be the finest of all the books produced past the Golden Cockerel Press, and began working on the sculpture Prospero and Ariel for the BBC's Broadcasting Business firm in London.[2] : 243 Throughout 1931 and into 1932, Gill worked on Prospero and Ariel, and four other works for the BBC, on site in primal London.[2] : 245 Carving in the open air up on scaffolding in the middle of London further increased Gill's public contour.[2] : 247 Although Gill had accustomed the BBC's choice of field of study affair when he took the commission he didn't see its relevance and ofttimes claimed that the figures he created represented God the Father and God the Son, the latter complete with the marks of the stigmata.[8] [31]

The Midland Hotel, Morecambe was congenital in 1932–33 by the London Midland & Scottish Railway to the Fine art Deco blueprint of Oliver Hill and included several works by Gill, Marion Dorn, and Eric Ravilious. For the projection Gill, with Lawrence Cribb and Donald Potter, produced two seahorses, modelled equally Morecambe shrimps, for the outside entrance; a circular plaster relief on the ceiling of the circular staircase inside the hotel; a decorative wall map of the north-west of England; and a big stone relief of Odysseus being welcomed from the body of water past Nausicaa for the entrance lounge.[32] While working in Morecambe, Gill met May Reeves, who became a regular company to Pigotts before moving there to run a small-scale schoolhouse and becoming Gill'southward resident mistress for several years.[ii] : 256

Jerusalem and Pigotts, 1934-1938 [edit]

Canaanite culture, the Rockefeller Museum, Jerusalem, 1934

In 1934 Gill, with Lawrence Cribb, visited Jerusalem to work at the Palestine Archaeological Museum, at present the Rockefeller Archaeological Museum.[2] : 263 [33] There they carved a stone bas-relief of the meeting of Asia and Africa to a higher place the front end entrance, together with 10 stone reliefs illustrating different cultures, and a gargoyle fountain in the inner courtyard. He also carved stone signage throughout the museum in English, Hebrew and Arabic.[33]

Gill'south two visits to Jerusalem had a profound impact on his state of mind. He became increasingly unhappy with the touch of humanity upon the world and as well go convinced of his own role as ane called by God to change society.[2] : 263 Returning to England, Gill's mood of cynicism deepened with the death of his son-in-police force, David Pepler, and he became increasingly antagonistic towards the Church and towards other artists.[2] : 265 Paradoxically, alongside this despondent world view Gill dropped his long-standing opposition to the use of modern domicile comforts and applicances. A bathroom was installed at Pigotts, a chauffeur and a gardener were appointed and his secretaries were allowed to use typewriters.[2] : 266 Religious observance was no longer expected of the workshop staff and among the additional apprentices and assistants Gill employed were a number of non-Catholics, including Walter Ritchie.[2] : 249 Prudence Pelham, the daughter of the Earl of Chichester, became Gill'southward but female apprentice.[2] : 250 During his career, Gill employed at least twenty-seven apprentices including his nephew John Skelton, Hilary Stratton, Desmond Chute, David Kindersley and Donald Potter.[viii] [22] [34]

Gill's 1935 essay All Art is Propaganda marked a complete reversal of his previous belief that artists should not concern themselves with political action.[2] : 272 He became a supporter of social credit and later moved towards a socialist position.[35] In 1934, Gill contributed fine art to an exhibition mounted past the left-wing Artists' International Association, and defended the exhibition against accusations in The Catholic Herald that its fine art was "anti-Christian".[36] Gill became a regular speaker at left-wing meetings and rallies throughout the second half of the 1930s.[ii] : 273 He was adamantly opposed to fascism, and was one of the few Catholics in United kingdom to openly support the Spanish Republicans.[35] Gill became a pacifist and helped set up the Cosmic peace organization Pax with Eastward. I. Watkin and Donald Attwater.[37] Later, Gill joined the Peace Pledge Union and supported the British branch of the Fellowship of Reconciliation.[35]

The Creation of Man, 1938

Gill was commissioned to produce a sequence of seven bas-relief panels for the façade of The People's Palace, now the Great Hall of Queen Mary Academy of London, which opened in 1936. In 1937, he designed the background of the first George Six definitive postage series for the post office.[38] [39] In 1938 Gill was commissioned to create a mammoth artwork for the Palace of Nations building in Geneva, equally the British Regime's gift to the League of Nations.[two] : 275 Gill's original proposal was to create a larger, international, version of the Moneychangers frieze that had caused such outrage in Leeds years earlier, but afterwards objections from delegates to the League, submitted an alternative scheme. The Creation of Human flanked past Human being's Gifts to God and God's Gifts to Man are three marble bas-reliefs in seventeen sections and establish the largest single work Gill created during his career merely are not considered among his finest works.[two] : 276 [40]

In 1935 Gill was elected an Honorary Associate of the Establish of British Architects and in 1937 was made a Regal Designer for Manufacture, the highest British award for designers, by the Royal Society of Arts, and became a founder-fellow member of the RSA'southward Faculty of Royal Designers for Industry when it was established in 1938.[2] : 271 In Apr 1937, Gill was elected an associate member of the Majestic Academy. Quite why Gill was offered, let alone accepted, these honours from institutions he had openly reviled throughout his career is unclear.[1]

Final works, 1939-1940 [edit]

St Peter the Apostle at Gorleston-on-Body of water, (1938–ix)

Altar of the Chapel of St George and the English Martyrs, Westminster Cathedral

During 1938 and 1939 Gill designed his simply complete piece of compages, the Roman Catholic Church of St Peter the Apostle at Gorleston-on-Sea.[1] He designed the building around a central altar which, at the time, was considered a radical departure from the Cosmic practice of the chantry beingness at the east end of a church.[two] : 280

Gill'due south last publications included 20-Five Nudes and Drawings from Life both of which included drawings of Daisy Hawkins, the teenage daughter of the Gills' housekeeper who Gill began an thing with in 1937.[1] The thing lasted 2 years during which time Gill drew her on an almost daily basis. When Hawkins was sent away from Pigotts, to the boarding house at Capel-y-ffin run past Betty Gill, Eric Gill followed her there to continue the relationship.[2] : 284

Amid Gill'southward final sculptures were a series of commissions for Guildford Cathedral. He spent time between Oct and December 1939 working at Guildford, on scaffolding carving the figure of St. John the Baptist.[one] He as well worked on a fix of panels depicting the stations of the cantankerous for the Anglican St Alban'due south Church in Oxford, finishing the drawings three weeks before he died and completing nine of the pieces himself.[41] [28] For the Chapel of Saint George and the English language Martyrs, in Westminster Cathedral, Gill designed a low relief sculpture to occupy the wall behind the altar.[xvi] Gill's design showed a life-sized figure of Christ the Priest on the cross attended by Sir Thomas More and John Fisher.[16] Gill died before the work was completed and Lawrence Cribb was tasked with finishing the piece past the Cathedral authorities who insisted he remove an element of Gill'south original blueprint, a effigy of a pet monkey.[xvi] When the chapel was eventually opened to the public this censorship of Gills' last work was a matter of some considerable controversy.[16]

From the end of 1939 into the middle of 1940, Gill had a series of illness, including rubella, but managed to write his autobiography that summer.[i] Gill died of lung cancer in Harefield Infirmary in Middlesex on the morn of Sunday 17 Nov 1940 and, later on a funeral mass at the Pigotts chapel, was buried in Speen's Baptist churchyard.[one]

After he died an inventory of over 750 carved inscriptions by Gill was compiled, in addition to the over 100 stone sculptures and reliefs, 1000 engravings, the several typeface designs he created and his 300 printed works including books, manufactures and pamphlets.[2] : 294

Sexual abuse [edit]

Gill'southward personal diaries reveal his child sexual practice abuse of his two eldest teenage daughters during their time at Ditchling Common, incestuous relationships with his sisters, and, in 1930, sexual acts on his dog.[10] [4] [42] This aspect of Gill'southward life was trivial known beyond his family and friends until the publication of the 1989 biography by Fiona MacCarthy.[43] An 1966 biography by Robert Speaight mentioned none of it.[43] Gill's daughter Petra Tegetmeier, who was live at the time of the MacCarthy biography, described her father as having "endless marvel well-nigh sexual practice" and that "we just took information technology for granted", and told her friend Patrick Nuttgens she was unembarrassed. The children were educated at abode and, co-ordinate to Tegetmeier, she was so unaware of how her father's behaviour would seem to others.[17] [44] Despite the acclamation the book received, and the widespread revulsion towards aspects of Gill'south sexual life that followed publication, MacCarthy received some criticism for revealing Gill'southward incest in his daughter's lifetime.[45] [46] Others, notably Bernard Levin, thought she had been likewise indulgent towards Gill.[43] MacCarthy commented:

after the initial shock, [...] as Gill'due south history of adulteries, incest, and experimental connection with his domestic dog became public knowledge in the belatedly 1980s, the consistent reassessment of his life and art left his artistic reputation strengthened. Gill emerged as ane of the twentieth century'southward strangest and most original controversialists, a sometimes infuriating, always absorbing spokesman for human being'south standing need of God in an increasingly materialistic civilisation, and for intellectual vigour in an age of encroaching triviality.[1]

Despite MacCarthy'south revelations, for several years Gill's reputation as an artist connected to grow but, following the exposure of a number of other high-profile paedophiles, this changed with groups and individuals calling for the removal of works by Gill.[47]

- In 1998 a group, Ministers and Clergy Sexual Abuse Survivors, called for the Gill's Stations of the Cross to be removed from Westminster Cathedral leading to a contend inside the British Cosmic press.[42] [3]

- Calls for Gill's statue of St Michael the Archangel to be removed from St Patrick's Catholic Church in Dumbarton.[47]

- In 2016 a number of residents in Ditchling objected to a proposal to erect a plaque by the hamlet war memorial which would have identified Gill as the maker of the monument.[47] [48]

- In January 2022 a human being climbed the façade of Broadcasting House and damaged the statue of Prospero and Ariel with a hammer, while another man shouted about Gill'due south paedophilia.[49] [l] Nearly 2,500 people had previously signed a petition, on the website 38 Degrees, asking for the work to be removed.[51]

- Guildford Cathedral announced in February 2022 that it was because an 'new interpretation' apropos Gill'due south statues of Saint John the Baptist and of Christ on the Cross which are on their edifice.[52]

- Several organisations, including Save the Children, resolved to stop using typefaces designed past Gill.[53]

When, in 2017, the journalist Rachel Cooke contacted a number of museums holding Gill's piece of work to question what, if any, impact the abuse revelations had on their policy towards showing cloth by him, the bulk refused to engage with her in whatever meaningful manner.[47] A notable exception was the Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft, which holds many examples of Gill'southward work and too Gill family unit objects. Previously, in October 2016, the museum had held a workshop, Not Turning a Blind Eye, with artists, curators and journalists invited to hash out how to address Gill's behaviour in its exhibition programme.[47] This resulted in a 2017 exhibition Eric Gill: The Body and a delivery by the museum to include at least i brandish highlighting Gill'due south offending in its permanent exhibitions.[47] [54]

Typefaces and inscriptions [edit]

In 1909 Gill carved Alphabets and Numerals for a book, "Manuscript and Inscription Letters for Schools and Classes and for the Use of Craftsmen", compiled by Edward Johnston. He later gave them to the Victoria and Albert Museum and then they could be used by students at the Regal College of Art. In 1914, Gill had met the typographer Stanley Morison, who was later to become a typographic consultant for the Monotype Corporation. Commissioned by Morison, he designed the Gill Sans typeface in 1927–30.[55] Gill Sans was based on the sans-serif lettering originally designed for the London Underground. Gill had collaborated with Edward Johnston in the early design of the Cloak-and-dagger typeface, merely dropped out of the projection before it was completed. In 1925, he designed the Perpetua typeface for Morison, with the uppercase based upon monumental Roman inscriptions. An in-situ case of Gill's design and personal cut in the style of Perpetua can be found in the nave of the church in Poling, W Sussex, on a wall plaque commemorating the life of Sir Harry Johnston.[56] In the menstruation 1930–31, Gill designed the typeface Joanna which he used to paw-ready his volume, An Essay on Typography.

-

Alphabets and Numerals (1909)

-

-

Gill Sans typeface

Gill's types include:

- Gill Sans, 1927–thirty; many variants followed

- Perpetua (design started c. 1925, starting time shown around 1929, commercial release 1932)

- Perpetua Greek (1929)[57]

- Gold Cockerel Press Blazon (for the Golden Cockerel Press; 1929)[58] Designed bolder than some of Gill's other typefaces to provide a complement to forest engravings.[59] [threescore] [61] [62] [63]

- Solus (1929)[64] [58]

- Joanna (based on work by Granjon; 1930–31, non commercially available until 1958)

- Aries (1932)[58]

- Floriated Capitals (1932)[58]

- Bunyan (1934)

- Pilgrim (recut version of Bunyan; 1953)[58]

- Jubilee (too known as Cunard; 1934)[58]

These dates are somewhat debatable, since a lengthy menstruum could pass between Gill creating a design and it existence finalised by the Monotype drawing function team (who would work out many details such as spacing) and cut into metal.[65] In addition, some designs such every bit Joanna were released to fine printing use long earlier they became widely available from Monotype.

One of the most widely used British typefaces, Gill Sans, was used in the classic design organization of Penguin Books and past the London and Due north Eastern Railway and later British Railways, with many boosted styles created by Monotype both during and after Gill's lifetime.[65] In the 1990s, the BBC adopted Gill Sans for its wordmark and many of its on-screen television graphics.

The family unit Gill Facia was created past Colin Banks as an emulation of Gill'due south stone carving designs, with separate styles for smaller and larger text.[66]

Gill was deputed to develop a typeface with the number of allographs limited to what could be used on Monotype systems or Linotype machines. The typeface was loosely based on the Arabic Naskh mode but was considered unacceptably far from the norms of Arabic script. It was rejected and never cut into type.[67] [68] [69]

Published works [edit]

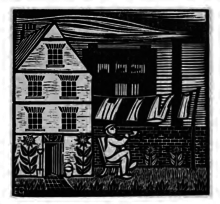

A Gill woodcut showing Hammersmith, illustrating the book The Devil'southward devices, or, Control versus Service by Hilary Pepler, 1915

Gill published numerous essays on the human relationship betwixt art and religion, and a number of erotic engravings.[70]

Gill'south published writings include:

- Christianity and Art, 1927

- Art-nonsense and other essays, Cassell 1929 (pocket edition 1934)

- Dress: An Essay Upon the Nature and Significance of the Natural and Artificial Integuments Worn by Men and Women, 1931[71]

- An Essay on Typography, 1931[72]

- Beauty Looks After Herself, 1933

- Unemployment, 1933

- Coin and Morals, 1934

- Fine art and a Changing Civilization, 1934

- Work and Leisure, 1935

- The Necessity of Belief, 1935

- Work and Property, 1937[73]

- Piece of work and Culture, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 1938

- Twenty-5 nudes, 1938[74]

- And Who Wants Peace?, 1938

- Sacred and Secular, 1940

- Autobiography: Quod Ore Sumpsimus [75]

- Notes on Postage Stamps [76]

- Christianity and the Machine Age, 1940.[77]

- On the Birmingham School of Art, 1940

- Last Essays, 1943

- A Holy Tradition of Working: passages from the writings of Eric Gill 1983.[78]

Gill provided woodcuts and illustrations for several books including:

- Gill, Eric (1925). Song of Songs. Waltham St. Lawrence, Berkshire: Gilt Cockerel Press.

- The Four Gospels. Golden Cockerel Printing. 1931. Facsimile edition published by Christopher Skelton at the September Press, Wellingborough, 1987.

- Chaucer, Geoffrey (1932). Troilus and Criseyde. Translated past Krapp, George Philip. New York: Literary Guild.

- Shakespeare, William (1939). Henry the Eighth. New York: Limited Editions Social club.

- The Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ, according to the iv evangelists. Hague & Gill Printers. 1934 Faber & Faber

Archive [edit]

Gill's papers and library are archived at the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library at UCLA in California, designated by the Gill family as the repository for his manuscripts and correspondence.[79] Some of the books in his drove have been digitised as function of the Net Archive.[80] Additional archival and volume collections related to Gill and his piece of work reside at the Academy of Waterloo Library[6] and the University of Notre Dame's Hesburgh Library.[81] Much of Gill's work and memorabilia is held and is on display at the Ditchling Museum of Art + Arts and crafts.

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j thousand l m northward o p q Fiona MacCarthy (25 September 2014) [23 September 2004]. "Gill, (Arthur) Eric Rowton". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v due west x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd exist bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg Fiona MacCarthy (1989). Eric Gill. Faber & Faber. ISBN0-571-14302-4.

- ^ a b James Williams (27 April 2017). "Eric Gill's fall from grace". Apollo . Retrieved nineteen January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Fiona MacCarthy (22 July 2006). "Written in rock". The Guardian . Retrieved ix November 2017.

- ^ a b c d east f chiliad h i j Ruth Cribb & Joe Cribb (2011). Eric Gill: Animalism for Letter of the alphabet & Line. The British Museum Press. ISBN978-0-7141-1819-2.

- ^ a b "Eric Gill archival and book collection". University of Waterloo Library . Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ "Eric Gill in Hammersmith" (PDF). Hammersmith and Fulham Celebrated Buildings Grouping Newsletter (33 (Winter 2015)): 6. 2015. Retrieved 13 Baronial 2021.

- ^ a b c d eastward Ruth Cribb (2007). "Eric Gill at the Victoria and Albert Museum New Sculpture Display". Antiques & Fine Fine art Magazine . Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Madonna and Child". National Museum Wales. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Fiona MacCarthy (17 October 2009). "Mad about sex". The Guardian . Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- ^ "Video of a Lecture at London University detailing Gill's interest in Indian Sculpture". London University School of Avant-garde Study. March 2012.

- ^ Rupert Richard Arrowsmith (2010). Modernism and the Museum: Asian, African, and Pacific Art and the London Advanced. Oxford University Press. pp. 74–103. ISBN978-0-19-959369-9.

- ^ a b Stephen Stuart-Smith (2003). "Gill, (Arthur) Eric (Rowton)". Grove Art Online. doi:x.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T032249. Retrieved 21 Jan 2022.

- ^ a b c d eastward f thou David V Barrett (5 August 2021). "Eric Gill: a moral problem". The Catholic Herald . Retrieved 12 Feb 2022.

- ^ a b Patrick Rogers (2005). "Stations of the Cross". Westminster Cathedral . Retrieved 20 Jan 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f chiliad h i Peter Doyle (1995). Westminster Cathedral 1895–1995. Geoffrey Chapman. ISBN0225666847.

- ^ a b Patrick Nuttgens (six January 1999). "Petra Tegetmeier obituary". The Guardian . Retrieved xix February 2016.

- ^ Historic England. "Trumpington War Memorial (1245571)". National Heritage List for England . Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ "War Memorials Register: Chirk". Royal State of war Museum . Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ Historic England. "Ditchling War Memorial (1438295)". National Heritage Listing for England . Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ Historic England. "Briantspuddle War Memorial (1171702)". National Heritage List for England . Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ^ a b Historic England. "Harting War Memorial (1438494)". National Heritage Listing for England . Retrieved vii March 2020.

- ^ "War Memorials Annals: Vıctoria and Albert Museum Staff − WW1". Imperial War Museum . Retrieved x February 2022.

- ^ "Memorial tablet commemorating Museum personnel killed in the Kickoff World War". Victoria & Albert Museum . Retrieved 12 Feb 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "Church of St Cuthbert (Roman Cosmic) (1376263)". National Heritage List for England . Retrieved xvi Feb 2022.

- ^ "Eric Gill - Christ driving the Moneychangers from the Temple". Academy of Leeds.

- ^ "War Memorials Annals: University of Leeds − WWI Eric Gill Frieze". Majestic War Museum . Retrieved 10 Feb 2022.

- ^ a b Martin Stott (viii December 2011). "Eric Gill in Oxford". Oxford Mail service . Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Peter Lord (2006). The Tradition A New History of Welsh Art 1400-1990. Parthian. ISBN978-1-910409-62-six.

- ^ "Catalogue entry: Mankind 1927-8". Tate. 2004. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ "Catalogue entry: Prospero and Ariel 1931". Tate . Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ Barry Guise & Pam Beck (2008). The Midland Hotel. Morecambe's White Hope. Lancaster, England: Palatine Books. ISBN978-1-874181-55-two.

- ^ a b "Eric Gill, 1882–1940". East Meets West: The Story of the Rockefeller Museum. Israel Museum. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ Donald Potter (1980). My Time with Eric Gill: A Memoir. Gamecock Printing. ISBN0-9506205-1-3.

- ^ a b c Martin Ceadel (1980). Pacifism in United kingdom, 1914–1945: The Defining of a Organized religion. Oxford, England: Clarendon Printing. pp. 281, 289–91, 295, 321. ISBN0-19-821882-six.

- ^ Charles Harrison (1981). English Art and Modernism 1900–1939. London: Allen Lane. pp. 251–2. ISBN0-253-13722-5.

- ^ Patrick 1000. Coy (1988). A Revolution of the Eye: Essays on the Catholic Worker. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 76. ISBN0-87722-531-1.

- ^ Peter Worsfold (2001). Great britain King George Half-dozen Low Value Definitive Stamps. The Groovy Britain Philatelic Society. ISBN0-907630-17-0.

- ^ "Eric Gill Postage Stamps by Type Designer". The Offices of Kat Ran Press . Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ "Lobby of the Council Chamber". United nations . Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ "Stations of the Cross past Eric Gill at St Alban's Church building". Ss Mary & John Churchyard . Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ a b Finlo Roher (v September 2007). "Can the art of a paedophile be celebrated ?". BBC News . Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- ^ a b c Fiona MacCarthy (24 July 2004). "Baptism past fire". The Guardian . Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ "The Darker Side of Ditchling". Brighton Argus. nine January 1999. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ^ Lottie Hoare (9 January 1999). "Petra Tegetmeier obituary". The Independent . Retrieved nineteen February 2016.

- ^ Barbara Harrison (7 May 1989). "A Lover's Quest for Fine art and God". The New York Times . Retrieved nineteen February 2016.

- ^ a b c d eastward f Rachel Cooke (9 April 2017). "Eric Gill: Can nosotros separate the artist from the abuser ?". The Observer . Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ Adrian Imms (one November 2016). "Villagers furious over plinth for paedophile sculptor". Brighton Argus . Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ Jim Waterson (12 Jan 2022). "Man uses hammer to attack statue on forepart of BBC Dissemination House". The Guardian . Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ Ruth Millington (16 Feb 2022). "Can you dissever the artist from the art ?". Art Great britain . Retrieved 23 Feb 2022.

- ^ Sabrina Johnson (12 Jan 2022). "Man takes hammer to BBC headquarters to blast statue by paedophile sculptor". Metro . Retrieved xiii January 2022.

- ^ Patrick Hudson (2 February 2022). "Eric Gill sculptures under scrutiny at Guildford Cathedral". The Tablet . Retrieved vi February 2022.

- ^ Catherine Bennett (16 Jan 2022). "Sometimes a statue is indefensible - the BBC should get rid of Eric Gill". The Observer . Retrieved 29 Jan 2022.

- ^ Michéle Woodger (12 May 2017). "Ditchling comes clean about Gill". The RIBA Journal . Retrieved eighteen February 2022.

- ^ Mosley, James (2001). "Review: A Tally of Types". Journal of the Printing History Society. London, England: Printing History Society. 3: 63–67.

- ^ "Johnston; Sir; Henry Hamilton (1858–1927); Diplomat and Explorer". The Natural History Museum. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ Harling, Robert (1978). The Letter Forms and Blazon Designs of Eric Gill. Boston, Massachusetts: D. R. Godine. ISBN0-87923-200-5.

- ^ a b c d e f "Eric Gill (1882–1940), Fonts designed by Eric Gill". Identifont. Archived from the original on 5 October 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ Mosley, James. "Eric Gill and the Cockerel Press". Upper & Lower Case. International Typeface Corporation. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ Brignall, Colin. "The Digital Development of ITC Golden Cockerel". International Typeface Corporation. Archived from the original on fourteen June 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ^ Carter, Sebastian. "The Gold Cockerel Press, Individual Presses and Private Types". International Typeface Corporation. Archived from the original on 21 May 2012. Retrieved eight Feb 2017.

- ^ Dreyfus, John. "Robert Gibbings and the quest for types suitable for illustrated books". International Typeface Corporation. Archived from the original on 21 May 2012. Retrieved 8 Feb 2017.

- ^ Yoseloff, Thomas. "A Publisher's Story". International Typeface Corporation. Archived from the original on xx May 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ^ Bates, Keith. "The Non Solus Story". Thou-Type. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ a b Rhatigan, Dan (September 2014). "Gill Sans after Gill" (PDF). Forum. Letter Substitution (28). Archived (PDF) from the original on fifteen February 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015. Dan Rhatigan is (or was) Type Director at Monotype.

- ^ Banks, Colin. "Gill Facia MT". Fontshop. Monotype. Retrieved xxx August 2015.

- ^ Blair, South.Due south. Islamic Calligraphy. p. 606, Fig. thirteen.7.

- ^ "Eric Gill" (PDF). The Monotype Recorder. 41 (3). 1958. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ^ Graalfs, Gregory (1998). "Gill Sands". Print.

- ^ Christopher Skelton (ed.), Eric Gill, The Engravings, Herbert Press, 1990, ISBN 1-871569-15-X.

- ^ Gill, Eric (1931). Clothes: An Essay Upon the Nature and Significance of the Natural and Artificial Integuments Worn by Men and Women. Jonathan Cape. OCLC 7320636.

- ^ Gill, Eric. (1931). An Essay on Typography ISBN 0-87923-762-vii, ISBN 0-87923-950-vi (reprints).

- ^ Gill, Eric (1937). Trousers & The Most Precious Ornament. London: Faber and Faber. OCLC 5034115.

- ^ Gill, Eric (1951). "Xx-5 Nudes". J. M. Paring & Sons.

- ^ Gill, Eric (1940). Autobiography: Quod Ore Sumpsimus. (published posthumously). Jonathan Cape. ISBN1-870495-13-6.

- ^ Gill, Eric. (2011). Notes on Postage Stamps Kat Ran Press, 2011. ISBN 0-9794342-i-ane.

- ^ In the series Christian Newsletter Books, The Sheldon Press.

- ^ Gill, Eric; Keeble, Brian (1983). A Holy Tradition of Working: passages from the writings of Eric Gill. Ipswich: Golgonooza Press. ISBN0-903880-xxx-X. (reprinted 2021 past Angelico Printing, ISBN 978-1-62138-681-0).

- ^ "Eric Gill Artwork Collection". Online Archive of California. William Andrews Clark Memorial Library. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ "Gill, Eric, 1882–1940, old owner". Cyberspace Archive. California Digital Library. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ "The Eric Gill Collection". Academy of Notre Matriarch Hesburgh Libraries. Rare Books & Special Collections. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

Further reading [edit]

- Attwater, Donald (1969). A Cell of Good Living. London: Chiliad. Chapman. ISBN0-225-48865-5.

- Bringhurst, Robert (1992). The Elements of Typographic Style. Hartley & Marks. ISBN0-88179-033-8.

- Collins, Judith (1998). Eric Gill: The Sculpture. Woodstock, NY: Overlook Printing. ISBN0-87951-830-8.

- Corey, Steven; MacKenzie, Julia, eds. (1991). Eric Gill: A Bibliography. St Paul'due south Bibliographies. ISBN0-906795-53-2.

- Dodd, Robin (2006). From Gutenberg to OpenType. Hartley & Marks. ISBN0-88179-210-i.

- Fiedl, Frederich; Ott, Nicholas; Stein, Bernard (1998). Typography: An Encyclopedic Survey of Type Pattern and Techniques Through History. Black Dog & Leventhal. ISBN1-57912-023-7.

- Fuller, Peter (1985). Essay: Eric Gill,: a Man of Many Parts. Images of God, The Consolations of lost Illusions. Chatto & Windus.

- Gill, Cecil; Warde, Beatrice; Kindersley, David (1968). The Life and Works of Eric Gill. Papers read at a Clark Library symposium, 22 April 1967. Los Angeles: William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, University of California.

- Peace, David; Gill, Evan, eds. (1994). Eric Gill: the inscriptions; a descriptive catalogue; based on the inscriptional work of Eric Gill. London: Herbert Printing. ISBN978-1-871569-66-seven.

- Harling, Robert (1976). The letter forms and blazon designs of Eric Gill. Westerham: Eva Svensson. ISBN0-903696-04-five.

- Holliday, Peter (2002). Eric Gill in Ditchling. Oak Knoll Printing. ISBN1-58456-075-iv.

- Kindersley, David (1982) [1967]. Mr. Eric Gill: Further Thoughts past an Apprentice. Cardozo Kindersley Editions. ISBN0-9501946-5-four.

- Macmillan, Neil (2006). An A–Z of Type Designers. Yale University Press. ISBN0-300-11151-7.

- Miles, Jonathan (1992). Eric Gill & David Jones at Capel-y-ffin. Bridgend, Mid Glamorgan: Seren Books. ISBN1-85411-051-9.

- Pincus, J.W; Turner Berry, W.; Johnson, A. F. (2001). Encyclopædia of Blazon Faces. London: Cassell Paperback. ISBNane-84188-139-ii.

- Skelton, Christopher, ed. (1990). Eric Gill: The Engravings. London: Herbert. ISBNone-871569-xv-X.

- Speaight, Robert (1966). Life of Eric Gill . London: Methuen & Co. ISBN0-416-28600-3.

- Thorp, Joseph (1929). Eric Gill. London: Jonathan Greatcoat. ASIN B0008B8S9Q.

- Yorke, Malcolm (1981). Eric Gill: Man of Flesh and Spirit. London: Constable. ISBN0-09-463740-vii.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eric Gill. |

- 65 artworks by or later Eric Gill at the Art UK site

- Biography of Gill on website of The Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic, with commentary on his 'unorthodox' estimation of Catholicism

- Manuscript & Inscription Messages, Edward Johnston, 1909 (plates by Gill)

- Portraits of Gill in the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Portraits by Gill in the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Prints and drawings by Gill in the British Museum drove

- Twenty-5 Nudes, Gill, 1938 (nerveless drawings)

- Troilus and Criseyde, Geoffrey Chaucer, translated by George Philip Knapp, 1932

- Works past Gill in the National Museum Wales collection (woodcuts by Gill)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eric_Gill

0 Response to "Who Is an Artist Who Used a Dog Head Stamp in His Art"

Post a Comment